Survey of Youth and Young Adults on Vocations: Part II. Consideration of a Vocation among Men

Consideration of Priesthood and Religious Life Among Never-Married U.S. Catholics by the Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate at Georgetown University - Washington, D.C.

Part II: Consideration of a Vocation among Men

This section of the report is specific to male respondents and their consideration of becoming a priest or religious brother.

Encouragement and Discouragement

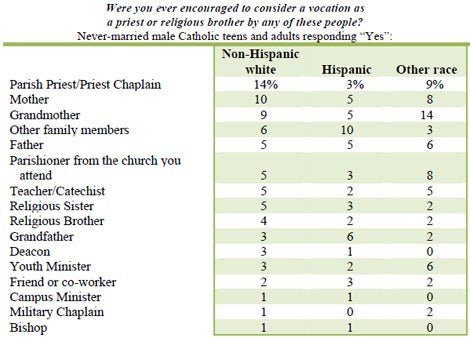

About one in ten or more non-Hispanic white male respondents say that they have been encouraged to become a priest or religious brother by a priest (14 percent), their mother (10 percent), or their grandmother (9 percent). As the table below shows, Hispanic respondents are less likely to have been encouraged to seek a religious vocation by these three types of individuals. Other race respondents are about equally likely as non-Hispanic white respondents to have received encouragement from these individuals.

Hispanic males are most likely to say they were encouraged by men in their family: a grandfather (6 percent), father (5 percent) and other family members (10 percent). Respondents of other races and ethnicities are most likely to say they were encouraged by their grandmother (14 percent), a priest (9 percent), their mother (8 percent), a parishioner (8 percent), or a youth minister (6 percent).

Respondents report an average of 0.7 people that encouraged them. This average is highest among non-Hispanic white males (0.8 encouragers). By comparison Hispanic males report 0.5 encouragers and those of other races indicate having 0.7 encouragers.

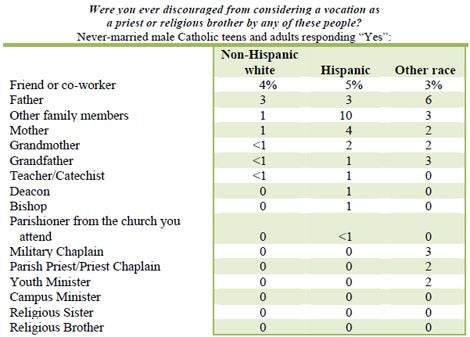

As shown in the table below, few male respondents indicate they received discouragement from considering the priesthood or religious life from anyone, overall. Hispanic males are the most likely to have received discouragement. One in ten indicated a family member, other than a parent or grandparent discouraged them. Across all groups, friends and fathers are the most common types of discouragers. Four percent of Hispanic males also noted receiving discouragement from their mother.

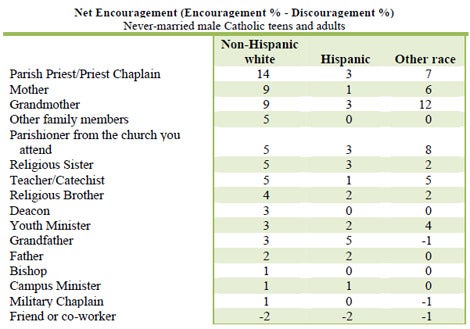

Subtracting the percentages of encouragement from discouragement we can calculate the “net encouragement” from each type of individual. As shown in the table on the next page, among non-Hispanic white males the individuals with the highest net encouragement levels are priests (+14 percentage points), mothers (+9 percentage points), and grandmothers (+9 percentage points). For Hispanic males, only grandfathers (+5 percentage points) provide net encouragement of at least 5 percentage points. Among those of other races and ethnicities the most positive net encouragement comes from grandmothers (+12 percentage points), priests (+7 percentage points), and parishioners (+8 percentage points).

For all three subgroups, friends tend to provide more discouragement than encouragement.

Vocations Presentation Made at School or Parish

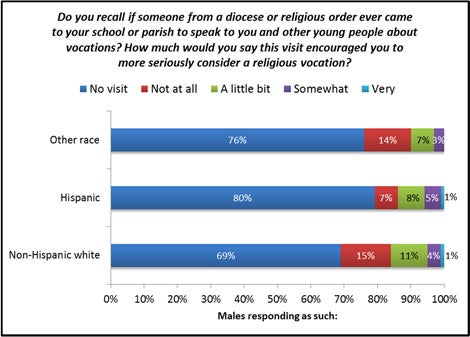

Most male respondents indicate that they do not recall anyone from a diocese or religious order ever coming to their parish or school to speak about vocations. Non-Hispanic white respondents are the most likely to recall a visit (31 percent) and Hispanic respondents are the least likely to do so (20 percent). Even among those who do recall such a visit, few say this encouraged them to consider a religious vocation “somewhat” or “very” seriously.

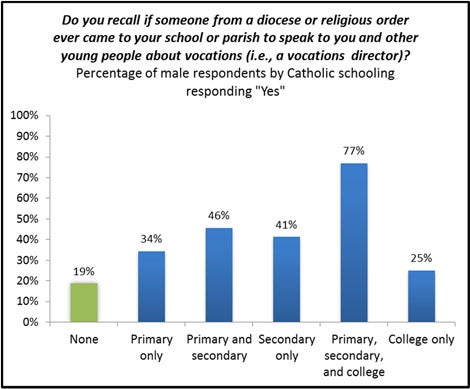

As the figure below shows, those who attended a Catholic educational institution are more likely than those who did not attend to report having seen a vocation presentation.

Participation in Church-related Programs, Groups and Activities

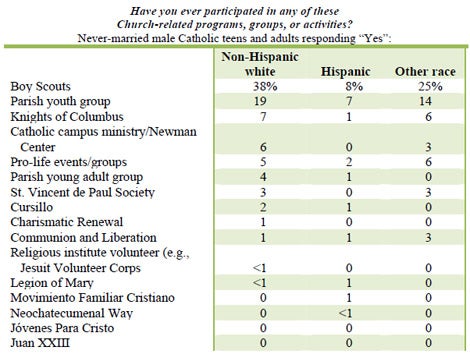

Four in ten non-Hispanic white male respondents (38 percent) say they were a Boy Scout. Only 8 percent of Hispanic male respondents indicate this, as do one in four male respondents of some other race and ethnicity (25 percent). Many also report being involved in a parish youth group (19 percent of non-Hispanic white males, 14 percent of other race males, and 7 percent of Hispanic males).

Small numbers of male respondents report being active in any other programs groups, or activities listed. Some report participation in the Knights of Columbus, college campus ministry, pro-life events and groups, and parish young adult groups.

Hispanic male respondents are generally less likely than other respondents to indicate involvement with any of the items listed (with the exception of Movimiento Familiar Cristiano).

Attitudes about the Church and Vocations

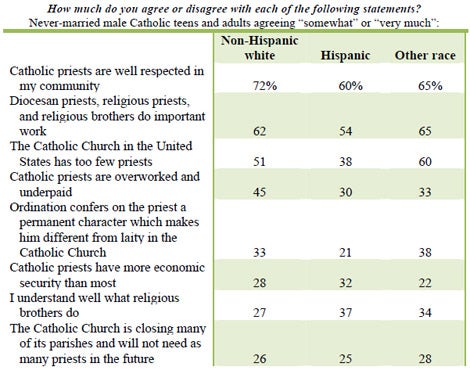

Majorities of male respondents are most likely to agree “somewhat” or “very much” that Catholic priests are well respected in their community and that priests and brothers do important work. Hispanic respondents, generally, are less likely than others to respond as such.

Many male respondents believe there is a priest shortage in the United States. A majority of non-Hispanic white respondents (51 percent) agree at least “somewhat” that there are too few priests in the United States. Only one in four (26 percent) agree “somewhat” or “very much” that the Catholic Church will need fewer priests in the future as it closes parishes. Hispanic respondents are slightly less likely than non-Hispanic white and other race respondents to agree at least “somewhat” that there are too few priests in the United States.

Consideration of Becoming a Priest or Religious Brother

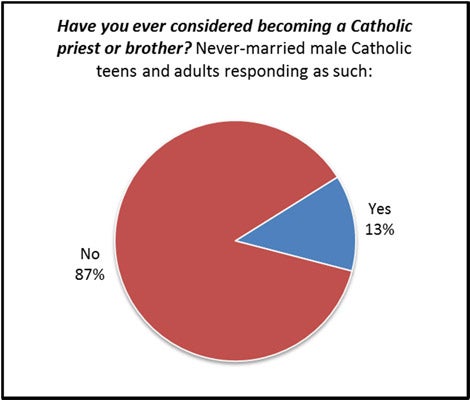

Overall, 13 percent of male respondents say they have ever considered becoming a priest or brother.

In 2003, when CARA first fielded this question in our national polls, 20 percent of male respondents indicated they had considered becoming a priest or brother. This dropped to 17 percent in a 2008 CARA survey. Although these differences are close to survey margins of sampling error, the pattern over time indicates the possibility that there is a slow erosion in males of ever having considered a priestly or religious vocation in the last decade.35 However, if this decline is real, it is likely related to generational changes with older Catholics, who may have been more likely to consider this in their youth, gradually being replaced by a younger generation who are not equally likely to consider this.

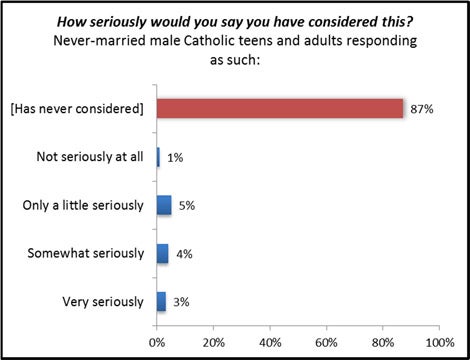

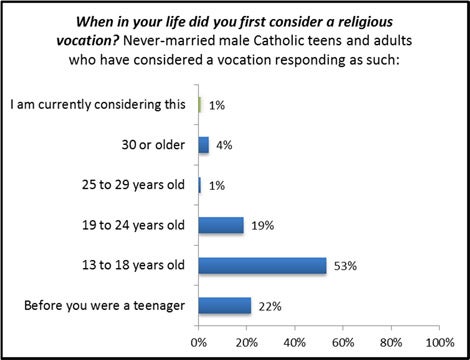

As the first figure on the next page shows, 7 percent of never-married Catholic males say they have “somewhat” or “very” seriously considered becoming a priest (3 percent “very serious” only). As the second figure shows, a majority (53 percent) say they first considered a vocation between the ages of 13 and 18—indicating that the experiences of male Catholics during their secondary school years may be among the most important. One in four (22 percent) indicates they considered this before their teen years and a similar percentage (19 percent) say they did so between the ages of 19 and 24.

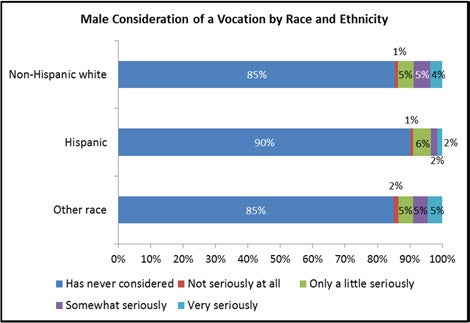

Hispanic males are the least likely to say they have ever considered becoming a priest or brother. However, the differences between these subgroups are not statistically significant.

Reasons for Not Considering a Vocation

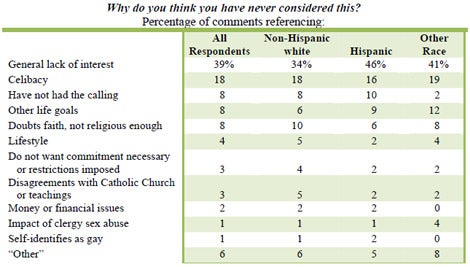

Respondents who say they have never considered becoming a priest or brother were asked, “Why do you think you have never considered this?” as an open-ended question. They could then respond in their own words. These comments have been categorized by theme. Overall, male respondents were most likely to reference a general lack in interest and celibacy for not considering a vocation as a priest or religious brother. Hispanic respondents are more likely than non-Hispanic white respondents to cite a general lack of interest (46 percent compared to 34 percent).

General lack of interest

Nearly four in ten (39 percent) cite a general lack of interest. Comments representative of this category include:

- Not my thing

- Eso no es para mi.

- The work is of no interest to me

- Never saw myself in this role

- Don’t want to

- Never thought of it

- No way

- It’s not a vocation that appeals to me

- It never crossed my mind

Celibacy

Nearly one in five (18 percent) cite celibacy as a reason for not considering a vocation. Comments representative of this category include:

- Celibacy

- I want to marry

- I like women too much

- Wanted to date women

- I am interested in having a family and not interested in preaching the faith

- Must have sex

- Wanted opportunity for romantic relations

- No poder tener pareja.

Have not had the calling

Fewer than one in ten (8 percent) indicate that they have not had the calling to become a priest or religious brother. Comments representative of this category include:

- People and even priests encouraged me, but I didn't feel the call

- I never felt a call to the religious life

- Wasn't my calling

- Not called by God and interested in different career

- I don't think that God is calling me to do that

- Didn't think I was called

Other life goals

Fewer than one in ten (8 percent) indicate that they have other life goals. Comments representative of this category include:

- Had other interests

- I have other things I want to become

- I’m not sure. I always thought about being a movie director, never have considered a religious job

- Because I want to be a marine biologist

- I have wanted to be a doctor like my dad since I was very young

- I want to be a police officer

Doubts faith, not religious enough

Fewer than one in ten (8 percent) say they either have doubts about their faith or do not feel religious enough. Comments representative of this category include:

- No devotion

- Because I am uncertain about religion

- I am not really a strong religious person, I just have Catholic beliefs

- Not very religious

- I'm not involved with the church enough to consider it

- Religion in my eyes has not been a high priority

- I'm not really into religious stuff

Other reasons

Fewer than one in 20 cited other reasons for not considering a vocation, including: issues about the lifestyle (4 percent), not wanting to make the commitment necessary or to have restrictions imposed on them (3 percent), disagreements with the Catholic Church or its teachings (3 percent), concerns about money or financial issues (2 percent), the impact of the clergy sex abuse (1 percent), or because they are gay (1 percent). Six percent provided a response that could not be classified into these other categories and there were not a sufficient number of similar responses to create another category.

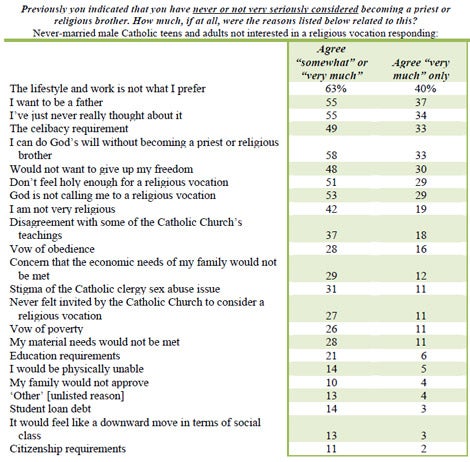

Respondents who said they have never considered becoming a priest or brother or who have but “not very seriously” were then provided a list of reasons from which to choose that would explain their lack of consideration. More than six in ten (63 percent) agreed “somewhat” or “very much” that this would not be a lifestyle and work that they would prefer. Majorities also agreed at least “somewhat” that they want to be a father (55 percent) or that they simply just never really thought about it (55 percent). Just under half cite celibacy (49 percent; compared to 18 percent citing this in response to the open-ended question).

Respondents also frequently cited the following for their lack of consideration: they can do God’s will without becoming a priest or brother (58 percent), that God is not calling them for a religious vocation (53 percent), they don’t feel holy enough (51 percent), or they would not want to give up their freedom (48 percent).

Forty-two percent agreed “somewhat” or “very much” that not being very religious is a reason for not considering a vocation. Only 37 percent agreed similarly that disagreement with Church teachings was a reason. Thirty-one percent cited the stigma of the clergy sex abuse issue (compared to 1 percent in response to the open-ended question). Only one in five (21 percent) cited educational requirements and 14 percent indicated student loan debt was an issue. Eleven percent cited citizenship requirements.

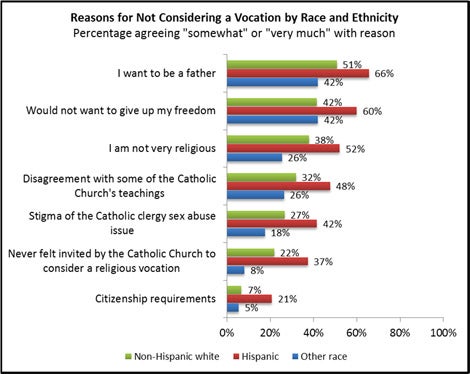

Non-Hispanic white males are slightly less likely than Hispanic and other race males to agree “somewhat” or “very much” that celibacy requirements are the reason they have never considered a vocation (41 percent compared to 50 percent of Hispanic and other race males). As shown below, there are several reasons that Hispanic respondents are more likely than others to cite for not considering a vocation. First among these is the desire to be a father (66 percent).36

Majorities of Hispanic respondents also say they do not want to give up their freedom (60 percent) and that they are not very religious (52 percent). Many other Hispanic respondents cite disagreement with Church teachings (48 percent) and the stigma of the clergy sex abuse issue (42 percent). More than a third (37 percent) agrees at least “somewhat” that they have never felt invited by the Church to consider a vocation and one in five (21 percent) similarly cites citizenship.

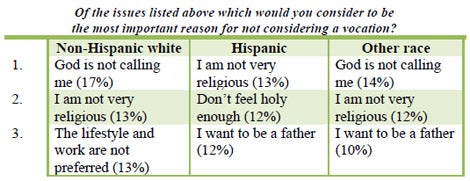

Respondents were asked to select one of the reasons that was most important to their lack of consideration. These are shown below for each race and ethnicity group. Hispanic and other race respondents selected wanting to be a father in the top three.

Reasons for Considering a Vocation

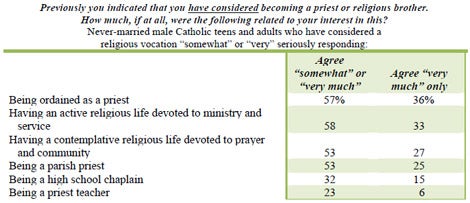

Among those male respondents that said they “somewhat” or “very much” considered becoming a priest or a religious brother, majorities agreed at least “somewhat” that they did so because they wanted to be ordained a priest (57 percent), because they wanted to have an active religious life devoted to ministry and service (58 percent), that they sought a contemplative religious life devoted to prayer and community (53 percent), or that they wanted to be a parish priest (53 percent).37

Of those male respondents who have considered a religious vocation, 31 percent indicate that they were considering a vocation for a specific religious order.

Eight percent of those indicating a specific order expressed interest in becoming a Jesuit. Another 8 percent indicated interest in becoming a Franciscan. Four percent indicated interest in becoming a Dominican. Many of the respondents who said they were considering a specific religious order simply responded “Catholic” or indicated they could not recall the specific order.

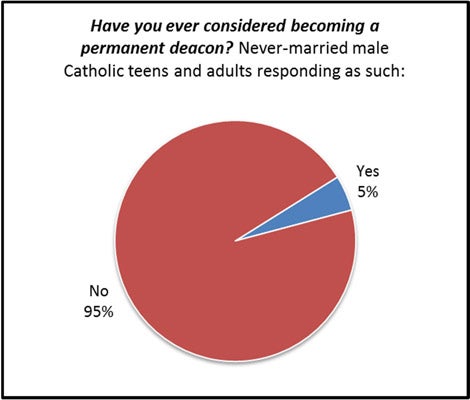

Consideration of Becoming a Permanent Deacon

Male respondents were asked if they had ever considered becoming a permanent deacon.38 Only one in 20 say they have considered this. Similarly, 5 percent of adult Catholic men (married and unmarried) responded as such in a CARA 2007 survey asking this question.39

Thus, fewer Catholic males consider becoming a permanent deacon than a priest or religious brother. However, this may be related to the age requirement for becoming a deacon. Given the rapid growth in the permanent diaconate in the United States in recent decades, it is also likely that many who consider becoming deacons follow through and seek out this vocation.

Non-Hispanic white respondents are the least likely to say they have considered becoming a deacon (3 percent compared to 6 percent of Hispanic respondents and 9 percent of other race respondents).

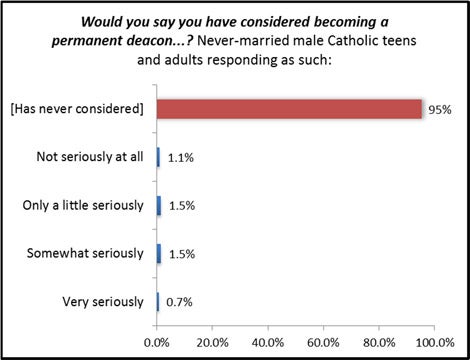

As the figure on the next page shows, among those who have considered becoming a permanent deacon, few have done so seriously.

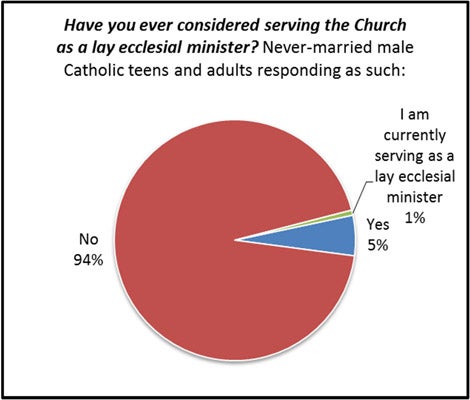

Consideration of Becoming a Lay Ecclesial Minister

Male respondents were also asked if they had ever considered becoming a lay ecclesial minister.40 Five percent of male respondents indicated they had considered this and 1 percent indicated they were already serving the Church in this capacity.41

Thus, fewer Catholic males consider becoming a lay ecclesial minister than a priest or religious brother. However, this may be related to the age at which lay ecclesial ministers often report feeling the “first call” to ministry.42

There are no statistically significant differences between racial and ethnic subgroups in consideration of becoming a lay ecclesial minister.

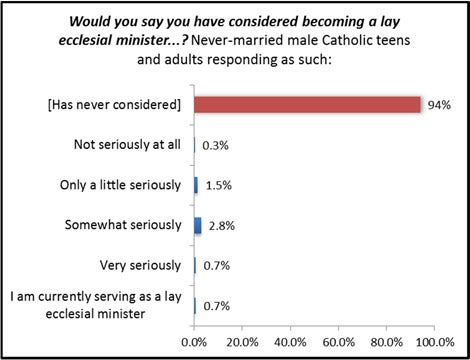

As shown in the figure below, 4 percent of never-married male Catholics say they have “somewhat” or “very” seriously considered becoming a lay ecclesial minister.

Footnotes

- It is important to note the sample for this survey includes never-married Catholic men, whereas the 2003 and 2008 survey included all Catholic adults.

- Although obviously related to the issue of celibacy, this is a distinct issue that is slightly more likely to be cited than celibacy more generally as a reason for not considering a vocation.

- There are too few respondents who have seriously considered a vocation to explore subgroup differences by race and ethnicity.

- After reading the following description: “A permanent deacon is an ordained man, either married or single, who may proclaim the Gospel, preach, and teach in the name of the Church, baptize, lead the faithful in prayer, witness marriages, and conduct wake and funeral services. Deacons are also leaders in identifying the needs of others, then marshaling the Church's resources to meet those needs.”

- Source: Sacraments Today: Belief and Practice among U.S. Catholics (pg. 71), https://cara.georgetown.edu/sacramentsreport.pdf

- After reading the following description: “A lay ecclesial minister is someone with professional training working or volunteering in a ministry at least part-time for a Catholic parish or other Church organization (for example, director of religious education, pastoral associate, youth minister, campus chaplain, or hospital chaplain).”

- CARA estimates that there are about 38,000 lay ecclesial ministers serving the U.S. Church (Source: The Changing Face of U.S. Catholic Parishes, pg. 60).

- The average age “parish leaders” report first hearing the call is 29 (Source: Perspectives from Parish Leaders: U.S. Parish Life and Ministry, pg. 42).